Israel has executed a convicted prisoner just once in modern history. Yet now, after October 7, 2023, a new push inside the Knesset is trying to make the death penalty not a historical exception, but a working tool of state power.

The argument is being sold as deterrence, closure, and national defense. The counterargument is being framed as discrimination, moral danger, and a legal system setting itself up for irreversible mistakes. In the middle are grieving families, lawmakers, and rights groups, all fighting over what justice is supposed to look like in a country that has spent decades avoiding executions.

The political punchline is the same one Israel has been wrestling with since the war began: the state wants maximum control over security outcomes, but it is also a democracy with courts, appeals, and internal divisions. A death penalty law would force those competing identities into the same room.

A Law With a Narrow Target and a Wide Blast Radius

According to BBC News, the new push is tied directly to the Hamas-led attacks on October 7, 2023, and the war that followed. The proposed law would target Palestinians convicted by Israeli courts of fatal terrorist attacks.

That targeting is the core of the controversy. Supporters describe it as a necessary tool against enemies who kill civilians. Opponents argue the bill is designed to apply to Palestinians, and not to Jewish Israelis, even in scenarios involving lethal violence.

In other words, one side is arguing for a stronger state. The other is arguing that the state is trying to formalize a two-track system of punishment.

The bill is also a political symbol. Israel already has harsh penalties, including life sentences, for terrorism offenses. So the fight is not only about whether killers should die. It is about what message the government wants to send, who it wants to send it to, and what kind of deterrence it believes in after a national trauma.

Inside the Knesset: Deterrence, Retribution, and a Sales Pitch

BBC News reports that the Knesset has held heated hearings that pulled in rabbis, doctors, lawyers, and security officials. The public face of the push includes lawmakers who argue that execution is not barbaric, but protective.

Zvika Fogel, the far-right chair of the parliamentary national security committee, framed it as part of an expanding security wall. “It’s another brick in the wall of our defence,” he told the BBC. “To bring in the death penalty is the most moral, the most Jewish and the most decent thing.”

That quote does a lot of work. It casts capital punishment as morality, tradition, and patriotism, all at once. It also makes the bill sound like a correction, not a revolution.

But Israel’s actual track record suggests the opposite. The country has had the death penalty on the books for certain crimes, yet executions have been nearly nonexistent. The rarity is not an accident. It is a policy choice that reflects legal caution, religious debate, and fear of wrongful execution.

A Grieving Mother’s Argument: Execution as Medicine

One of the most emotionally specific arguments for the bill comes from people who lived through the October 7 attack in the most personal way.

BBC News describes testimony from bereaved families, including Dr Valentina Gusak, whose 21-year-old daughter, Margarita, was killed with her boyfriend, Simon Vigdergaus, as they fled the Nova music festival in 2023.

Gusak endorsed the bill, and she did it with a framing that turns punishment into prevention. “In my view, only 10 or 20 per cent of the law is intended for justice, and the remaining percentage is deterrence and prevention,” she told the BBC.

Then she sharpened the argument into a slogan that has traveled far beyond the committee room: “It’s a vaccine against the next murder, and we must ensure the future of our children.”

The power dynamic here is obvious. The state is considering the most final tool it has. The moral pressure comes from victims’ families who believe the state failed to protect them once and should not hesitate again.

Israel Has Executed Once, and It Still Haunts the Debate

Opponents of the bill do not have to argue theory. They can point to history.

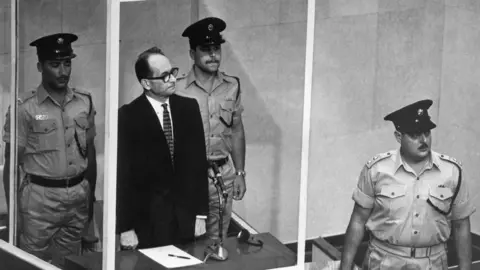

BBC News notes that Israel has used the death penalty against a convicted prisoner only twice in its history, with the last execution more than 60 years ago: the hanging of Adolf Eichmann, the Nazi SS officer and Holocaust architect captured in Argentina and tried in Jerusalem.

The Eichmann case is often treated as its own category, because it was: a singular crime, a singular defendant, and a singular national mission of historical justice. If supporters of the new bill want to argue that executions belong in Israeli law, they have to confront what Israelis tend to remember about the last execution: it was tied to the Holocaust, not to modern terrorism cases debated in parliament.

BBC News also recounts another execution, the 1948 case of Meir Tobianski, a military captain executed for treason after a makeshift court martial, then posthumously exonerated. That detail lands like a warning label. It is the nightmare scenario in capital punishment debates, turned into a local precedent.

The Rights Groups’ Charge: A Death Penalty for 1 Population

BBC News reports that human rights groups have called the bill “one of the most extreme legislative proposals” in Israel’s history, objecting on ethical and legal grounds, and warning about discrimination if the law is designed to apply only to Palestinians.

Tal Steiner, executive director of the Israeli NGO HaMoked, put the objection bluntly. “The fact that we’re even re-discussing bringing this back into the legal system in Israel is itself a low point,” she told the BBC.

Then she went straight to the most politically combustible claim about the bill’s design: “Beyond that, our objection is that the law is racially designed, meant to apply only to Palestinians, never to Jews, only to people who kill Israeli citizens, never, for example, to Israeli citizens who kill Palestinians. The motivation is clear.”

That is not just a moral accusation. It is a legal strategy, too. If the bill moves forward, the fight is likely to turn on whether a system that is supposed to treat defendants equally is creating a punishment lane for one group.

What the Bill Says It Is Doing

BBC News describes the draft legislation’s stated purpose as protecting Israel, “its citizens and its residents,” while “increasing deterrence against the enemy.” The draft also aims to reduce incentives for kidnappings or hostage-taking meant to secure the release of prisoners, and it mentions “providing retribution” for criminal acts.

That mix of goals is revealing. Deterrence is forward-looking, trying to stop the next attack. Retribution is backward-looking, trying to answer the last one. Hostage logic is strategic, an attempt to reduce bargaining leverage. Put together, the bill is not a single-purpose law. It is a policy bundle responding to a trauma, and also trying to reshape incentives in a war environment.

But the more goals a law claims, the more contradictions it inherits. If executions are framed as deterrence, the key question becomes whether they deter. If they are framed as retribution, the key question becomes whether the state should kill to prove it is strong. If they are framed as hostage prevention, the key question becomes whether they change the calculation of armed groups, or inflame it.

Why This Fight Matters Beyond Israel

Capital punishment fights are never just about criminal justice. They are about what a state says it is allowed to do when it feels endangered, and who counts as fully protected by the law.

Israel is also arguing this in public, in parliament, and through civil society organizations, while facing intense global scrutiny over the Gaza war and its broader conflict with Palestinians. A death penalty law that is perceived as group-specific would not stay contained as a domestic debate. It would become part of Israel’s international narrative battle over rights, security, and equal treatment.

Supporters want the law to read as serious. Opponents want it to read as unequal justice. Both sides understand that whichever story sticks has consequences, from court challenges to diplomacy.

What to Watch Next

The immediate question is whether the proposed law advances through Israel’s legislative process and whether it triggers legal challenges that force courts to weigh in on equality, due process, and the state’s authority to execute.

The longer question is whether the bill is meant to pass or meant to signal. In many political systems, especially during wartime, the loudest bills serve two audiences at once: voters demanding strength and adversaries being warned about consequences.

Either way, Israel’s death penalty debate is no longer a dusty historical footnote about Eichmann. It is a live argument about what the state will do now, and who the state is willing to do it to.