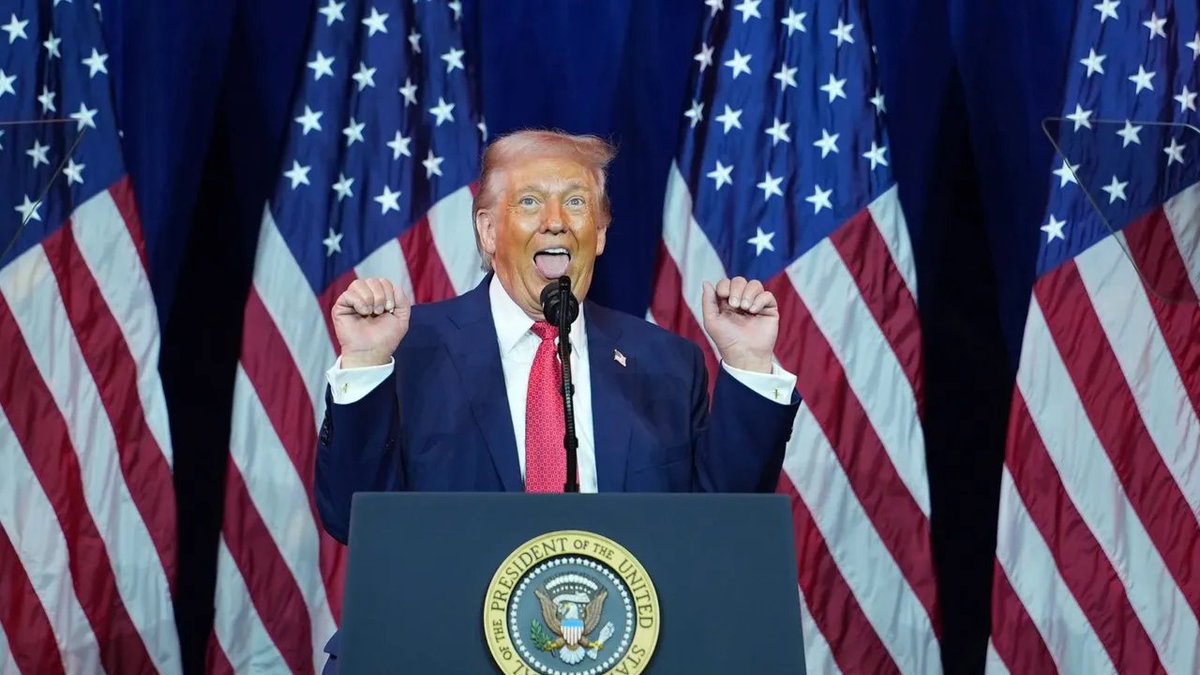

President Trump says the second wave of U.S. attacks on Venezuela was coming. Then, suddenly, it was not. The pivot landed as the Senate moved to fence in his war powers and as oil executives prepared for a White House meeting with Venezuela hanging over the agenda.

That combination has Washington asking the same question from two directions. Is Venezuela about national security, or is it also about barrels, leverage, and who gets to decide when the United States uses force?

A Pause Button, and a Reason That Raises Eyebrows

In remarks cited by CBS News, Mr. Trump said he has “cancelled the previously expected second Wave of Attacks” on Venezuela because Venezuela has been “working well together” with the U.S.

Even for a president who often treats foreign policy as a rolling negotiation, the phrasing is a tell. “Working well together” is diplomatic language. It is also the kind of language that immediately invites follow-up questions, such as: Working together on what, exactly, and under what enforcement mechanism?

When CBS News asked whether the Venezuela strikes were part of a broader foreign policy doctrine, Mr. Trump answered with a different framing, one rooted in domestic harm. “No, it’s a doctrine of ‘don’t send drugs into our country,'” he said.

Those two explanations are not identical. One suggests de-escalation through cooperation. The other signals a simple enforcement line tied to drugs and border security. That tension is now colliding with congressional skepticism.

The Senate’s Rare Bipartisan Check

According to CBS News, the Senate voted to advance a resolution that would limit future strikes on Venezuela, with five Republicans joining Democrats. On Capitol Hill, that kind of cross-party alignment on presidential war powers is uncommon, and that is precisely why it matters.

The mechanics still matter, too. Advancing a resolution is not the same as forcing an immediate policy reversal. But it is a bright flare from lawmakers who believe the White House is stretching its authority, or at least acting with insufficient consultation.

Congress has long wrestled with how far a president can go without explicit authorization. The modern debate often turns on the War Powers Resolution of 1973, which was designed to require notification and set time limits when U.S. forces are introduced into hostilities, unless Congress authorizes the action. Presidents of both parties have argued over how that law applies to real-world operations. This Senate vote signals that, on Venezuela, lawmakers want their fingerprints on the next step.

Oil Executives at the White House, and the Venezuela Question

At the same time, Mr. Trump is planning to meet with oil industry executives at the White House, CBS News reported. The list of expected attendees includes executives from Halliburton and Exxon, among others.

The reported purpose is also unusually direct. CBS News said the administration is pressing oil companies to re-enter Venezuela. That is not a casual diplomatic sidebar. It is a major policy goal with implications for sanctions enforcement, corporate risk calculations, and the optics of American business stepping back into a country still defined by political crisis.

It also places corporate America in the middle of a three-way tug-of-war. On one side is the White House, pushing for energy-related engagement. On another is Congress, signaling that military escalation should not be a solo executive project. On the third is Venezuela’s internal power structure, where President Nicolas Maduro’s loyalists, according to the CBS News report, remain in charge.

For companies, Venezuela is not just a map location. It is a sanctions and compliance minefield. Any serious “reentry” effort quickly becomes a question of what the U.S. government permits, what it can enforce, and what will change depending on elections and court fights at home.

Machado Meeting Teased, and the Opposition Dilemma

Then there is the opposition angle. Mr. Trump said he plans to meet Venezuelan opposition leader Maria Corina Machado next week, CBS News reported. That meeting matters because Washington has spent years trying to evaluate, and sometimes influence, which Venezuelan political figures could realistically shift the balance of power.

But even here, the White House’s messaging has not been linear. CBS News noted that Mr. Trump recently suggested Machado did not have enough support to replace Maduro loyalists who remain in charge. That is a blunt assessment, and it cuts against a common political storyline that one opposition figure, blessed by international attention, can quickly replace an entrenched governing apparatus.

If the opposition lacks the leverage to dislodge Maduro’s circle, then U.S. policy choices narrow fast. They often collapse into three imperfect tools: sanctions, diplomacy, or force. The current news cycle suggests the administration is trying to keep all three on the table while taking heat for how that menu gets chosen.

Two Storylines That Do Not Fully Match

Put the pieces together and the contradictions sharpen.

The president says he canceled the next attack wave because Venezuela is “working well together” with the U.S. Yet he also describes the strikes as part of a “don’t send drugs into our country” doctrine, which implies a continuing enforcement posture rather than a mutual detente.

Meanwhile, the Senate is moving to limit future strikes, suggesting lawmakers worry the White House could widen military action, or at least act again without the kind of congressional buy-in that makes a campaign durable.

And while that debate is raging, the administration is reportedly pushing oil companies to reenter Venezuela, a move that can look like pragmatic energy policy to supporters and like a geopolitical bargain to critics. Is the U.S. squeezing Caracas, or coaxing it? Is the policy designed to punish the regime, or to extract concessions, or to stabilize flows and influence? The public cues right now point in multiple directions at once.

Why Washington Is Suddenly Obsessed With ‘Who decides’

There is a reason war powers votes break through the noise. They are not just about a single country. They are about precedent.

If Congress can corral a president’s ability to strike Venezuela, it sends a message about other flashpoints too. If it fails, it can normalize a model where lawmakers complain after the fact, while the executive branch banks on speed and ambiguity.

For Mr. Trump, the stakes are also political. A doctrine centered on stopping drugs is easily communicated to voters. It shifts the focus from faraway governance problems to domestic consequences. But as soon as the White House is also seen courting the oil industry on Venezuela, critics have a ready-made counterargument that the policy is about more than narcotics interdiction.

What To Watch Next

Three moments will clarify whether this is a true pivot or simply a pause.

First, the White House meeting with oil executives. Watch for any public readout that indicates whether “reentry” means a sanctions shift, specific licenses, or simply a pressure campaign on companies to position themselves for a future change.

Second, the Senate’s war powers effort. Advancing a resolution is a warning shot. The next steps will show whether lawmakers can turn rare bipartisan discomfort into a real constraint.

Third, the promised meeting with Maria Corina Machado. If it happens, the substance will matter more than the photo. A meeting that produces a clear U.S. policy line is one thing. A meeting that produces competing signals, or no signal at all, leaves the same vacuum that Congress is trying to fill.

For now, the most revealing line remains the president’s own. “No, it’s a doctrine of ‘don’t send drugs into our country,'” Mr. Trump told CBS News. The Senate’s response suggests many lawmakers are not convinced doctrine alone can substitute for permission.