The world got used to a referee. Now it looks more like a street fight with three heavyweights and a lot of nervous onlookers.

That is the quiet tension running through a sweeping BBC analysis of a world “inching back to a pre-WW2 order,” and the looming problem for “middle powers” caught between Washington, Beijing, and Moscow. The essay is personal, almost confessional, and then it turns into a warning label for the next decade.

At the center is a question that keeps getting louder: if the big powers are done playing by rules, who exactly enforces the rules?

A 2002 memory that now reads like a forecast

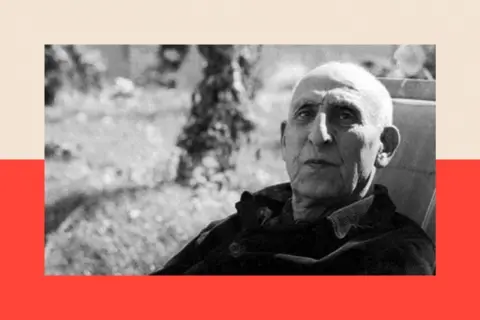

The BBC piece, written by senior correspondent Allan Little, opens in January 2002 at Columbia Journalism School, with New York still raw after 9/11. Little tells the room he was “born 15 years after the Second World War” in “a world America made,” crediting the US with Western Europe’s postwar security and prosperity. Then he notices a young man in the audience crying.

Afterward, the student approaches him with a line that lands harder today than it likely did then: “America needs to hear this stuff from its foreign friends.”

In Little’s telling, that moment captured something his generation inherited almost by accident: an international system “regulated by rules,” designed to prevent the unconstrained domination of great powers.

As the world inches back to a pre-WW2 order, the ‘middle powers’ face a grave new challenge https://t.co/raoXNxhy9f pic.twitter.com/urh3CE1ckR

— World News (@Worldnews_Media) January 25, 2026

How the US built the postwar house, and where the walls are cracking

The rules-based order was not a single treaty. It was an architecture, built in chunks: the UN Charter, security alliances, trade systems, and financial plumbing laid in the wake of catastrophe. The US helped drive the creation of institutions like the International Monetary Fund and backed Europe’s reconstruction with the Marshall Plan.

That story is the flattering version. The BBC essay also flags the less flattering truth that has always lived alongside it: the US, like other great powers, broke rules when it felt strategic necessity. The BBC article references the 1953 Iran coup against Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq, an episode documented in the US State Department’s historical record on US-Iran relations and the 1953 coup.

And in the Western Hemisphere, Washington’s long-running insistence on a special sphere of influence goes back to the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, which still echoes in today’s arguments about borders, bases, and who gets to “belong” where.

Little’s point is not that the order was pure. It is that the order existed, and that even hypocritical powers often felt compelled to justify themselves in its language.

The new problem for “middle powers” is not ideology; it is leverage

“Middle powers” is a slippery label, but it usually means countries with real capacity and global interests, yet not enough raw power to dictate outcomes alone. Think Canada, Australia, Japan, South Korea, the UK, and big European states. They have advanced militaries, trade reach, and diplomatic networks. What they do not have is the luxury of ignoring the giants.

In the BBC analysis, this group is framed as facing a “grave new challenge” as the system shifts toward something more reminiscent of pre-World War II balance-of-power politics. The image captions in the BBC package also point to the idea that middle powers should act in concert, citing a Davos speech attributed to Mark Carney, described there as Canada’s prime minister. The detail matters less than the signal: elite forums are now openly debating coalition-building among countries that do not want to pick a single patron.

“This year’s World Economic Forum (WEF) carried sharper edges. Donald Trump arrived sowing discord—pressuring Europe, criticizing NATO, and floating U.S. control of Greenland—while Canada’s Mark Carney warned middle powers of a global order losing its grip.” https://t.co/9ES72jDm4Y pic.twitter.com/5dDcuQIbJW

— Andrew Man (@TegoArcanaDei) January 24, 2026

The strategic bind is familiar. Middle powers benefit from trade with China, security ties with the US, and energy or geography constraints that pull them toward regional compromises. When the big powers squeeze, middle powers often pay first.

Trump’s NATO pressure campaign, and the uncomfortable part: It worked

One of the BBC article’s sharper contrasts is the argument that Donald Trump’s blunt message to allies about burden-sharing produced results where gentler diplomacy did not. That argument runs into a complicated reality. NATO members did formalize a benchmark in 2014 for allies to aim to spend 2 percent of GDP on defense, documented in NATO’s Wales Summit Declaration.

Middle powers such as the UK have the most to lose in Trump’s unstable global order, to thrive we must look to building relationships built on genuine co-operation, writes Mhairi Black✍️

🔗https://t.co/w3fg40O0Ms pic.twitter.com/4Pn8hp9qxs

— The National (@ScotNational) January 24, 2026

It is also true that European defense spending has risen in recent years, and NATO publicly tracks those figures in its defence expenditure reports and summaries. Trump did not invent the debate, but he did turn it into a loyalty test, and middle powers inside alliances had to decide whether to treat his demands as transactional bullying or overdue reality.

Here is the part that middle powers worry about: if alliance commitments become a series of price tags, then deterrence becomes negotiable. The question shifts from “What happens if we are attacked?” to “What are we worth this quarter?”

Great power muscle memory is coming back, and it is not just America

Middle powers are not only reacting to Washington. They are reacting to a broader return of great power muscle memory: wars of territorial revision, coercive trade, cyber sabotage, and the kind of “zone defense” diplomacy where major states treat neighbors as buffers.

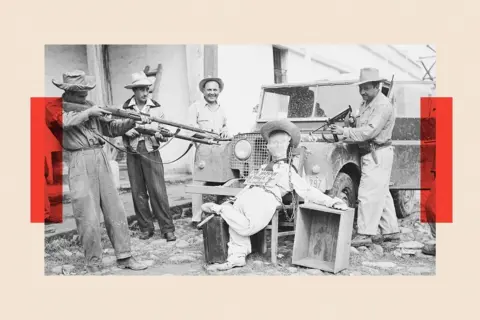

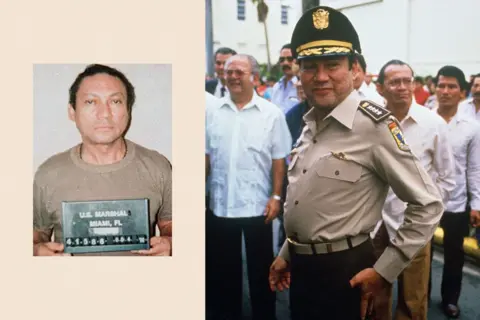

The BBC essay’s historical references underline that this is not new behavior. It is old behavior returning to a world where enforcement is weak. In the late Cold War, for example, the US invaded Panama to depose Manuel Noriega, a major episode summarized in the US State Department historical office’s timeline on US policy and the 1989 Panama intervention. The point is not to relitigate every intervention. It is to show what great powers do when they believe they can.

China and Russia have their own histories and methods. The practical effect for middle powers is the same: pressure arrives from multiple directions, and the cost of defiance rises.

So, what can “middle powers” actually do?

The BBC framing implicitly dares middle powers to stop acting like audiences and start acting like organizers. That means three concrete moves, none of them easy.

First, coordinate economic defenses. Supply chain security, investment screening, and technology controls are already becoming group projects, not solo acts. Countries with similar risk profiles can blunt coercion by moving together.

Second, build minilateral security networks that complement big alliances. Not every security problem fits inside NATO, and not every Indo-Pacific deterrence move needs to be routed through Washington. Smaller groupings can be faster, more flexible, and harder to split.

Third, invest in credibility at home. Middle powers cannot preach rules abroad while their own politics treat institutions as disposable. The reason the postwar story mattered is that it offered a moral vocabulary that could be exported. If that vocabulary turns into a partisan prop, it stops working.

The contradiction that the BBC essay does not let you ignore

Little’s Columbia story is a snapshot of American soft power at its peak, when even grief was a kind of glue. But the essay also carries a darker truth in the background: the rules-based order was partly sustained by US power, and that means it can be weakened by US choices, whether through isolationism, transactional alliances, or selective enforcement.

That is why the student’s line still stings. “America needs to hear this stuff from its foreign friends.” The subtext is that friends may need to hear something too: the era of assuming the referee always shows up is ending.

Middle powers now face a choice that will define their relevance. Act together, or accept terms set elsewhere. The BBC essay does not pretend there is a clean third option.

References

-

- BBC News, “As the world inches back to a pre-WW2 order, the ‘middle powers’ face a grave new challenge”

- US State Department, Office of the Historian, “The Marshall Plan, 1948”

- United Nations, “Charter of the United Nations”

- International Monetary Fund, “History: The IMF at a Glance”

- US National Archives, “Monroe Doctrine (1823)”

- NATO, “Wales Summit Declaration (2014)”

- NATO, “Defence expenditure of NATO countries”