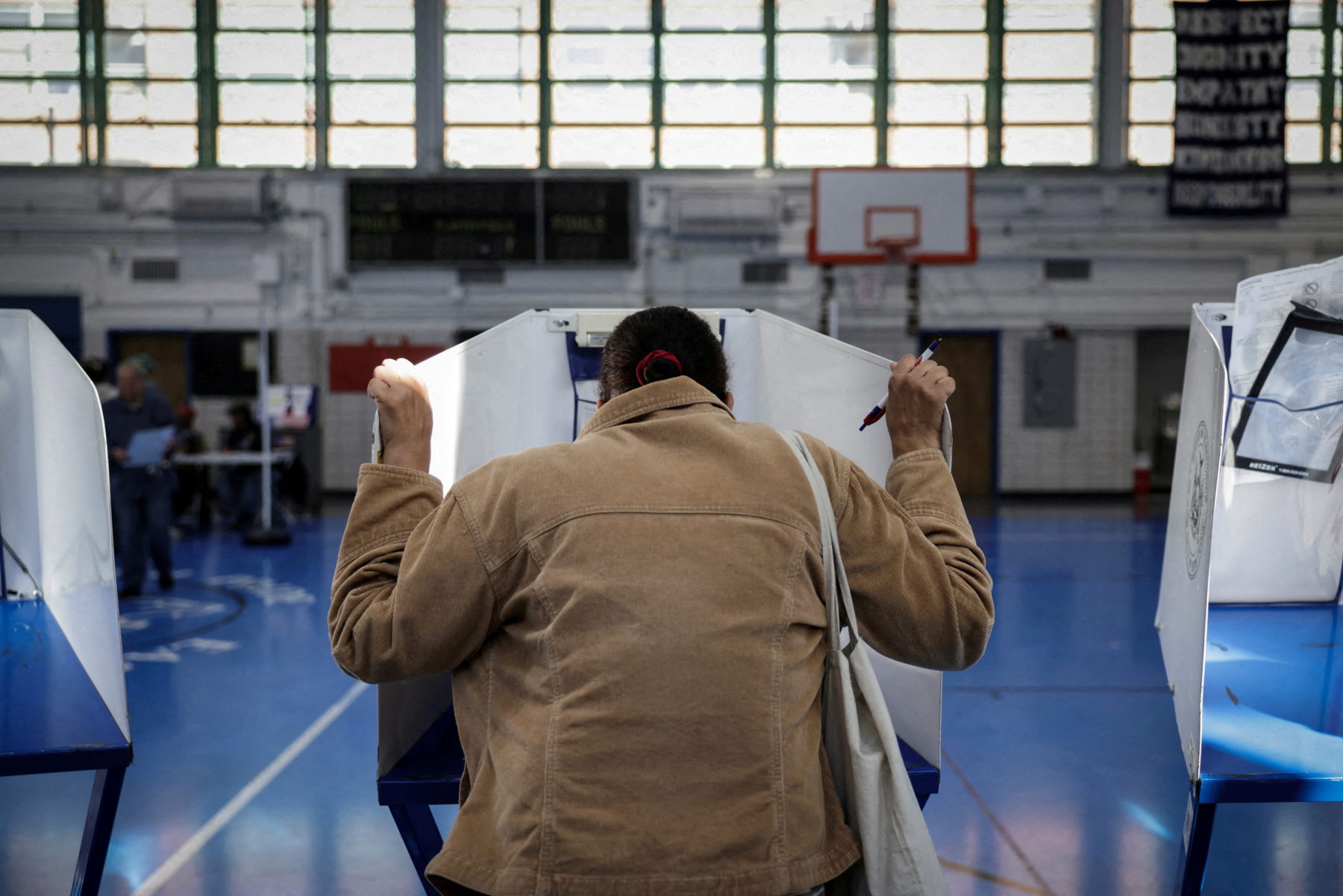

Republicans say the SAVE America Act is about one simple idea: only citizens vote. The fight is over the not-so-simple part: who has to prove it, with what documents, and what happens to the officials caught in the middle.

What You Should Know

The SAVE America Act would require documentary proof of U.S. citizenship for federal voter registration and tighten photo ID rules for in-person and absentee voting. Voting rights groups warn it could keep eligible citizens off the rolls, while the bill faces uncertain prospects in the Senate.

The legislation is backed by President Donald Trump and promoted by House Republicans as an election-integrity fix ahead of the 2026 midterm elections. It is also a bet that the politics of suspicion will beat the logistics of actually running elections in 50 states and the District of Columbia.

The Pitch: A Citizenship Message, Plus a Trump-Era Grievance

The public argument is clean and repeatable. In a post supporting the bill, the White House put it this way: “American citizens, and only American citizens, should decide American elections.”

That line lands because noncitizen voting in federal elections is already illegal, and it has been for more than a century. It also lands because voter ID, broadly defined, polls well. Republicans, including Rep. Chip Roy of Texas, have framed the SAVE Act as a basic guardrail, not a rewrite.

The political subtext is less tidy. Trump has spent years describing U.S. elections as “rigged” and “stolen” without evidence of widespread voter fraud. In that world, a proof-of-citizenship mandate is not just a policy tool. It is a loyalty test, a messaging weapon, and a way to keep the “fix the elections” drumbeat alive even when courts, audits, and election administrators say the crisis is not there.

Trump has also floated a much bigger idea, urging the federal government to “nationalize” elections, a direct collision with the Constitution’s state-run election framework. The SAVE Act is not that. However, it travels the same political highway: Washington stepping deeper into rules that states have traditionally administered.

The Fine Print: What the SAVE Act Actually Changes

The SAVE America Act is built around a demand that sounds straightforward until it hits real life. To register to vote in federal elections, Americans would need documentary proof of citizenship. For many people, that means a passport or a birth certificate.

Supporters point out that the bill lists multiple acceptable documents. Critics counter that some of those options are more theoretical than practical, depending on what states issue, what they print on IDs, and whether records match current legal names.

One flash point is REAL ID. The bill includes a pathway that references a REAL ID-compliant identification that indicates U.S. citizenship. Voting policy experts have warned that REAL IDs are issued to citizens and noncitizens, and that state IDs generally do not explicitly label citizenship status.

Then there is the second punch: identification at the moment of voting.

- The bill would require a government-issued photo ID to vote in person.

- It would also require providing a copy of an eligible photo ID when requesting an absentee ballot and when submitting it.

- It includes requirements that can force some mail registrants to show proof of citizenship in person.

- It directs states to take steps aimed at ensuring only U.S. citizens are registered.

None of that is abstract to the people who run elections. It is staffing, training, documents, scanning, photocopy rules, deadlines, and databases. It is also litigation bait, because every new rule creates a new set of edge cases.

The hardest edge case is the bill’s criminal penalty provision. The SAVE Act would add penalties for election officials who register an applicant who does not provide documentary proof of citizenship. According to election administration analysts at the Bipartisan Policy Center, the risk is that officials face potential punishment even in scenarios involving eligible citizens if the paperwork does not satisfy the statute.

Rachel Orey, who leads the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Elections Project, called that a dangerous gray zone because it leaves “vague discretion” with frontline officials who could be punished for getting it wrong. In practical terms, the fear is not that officials will recklessly register noncitizens. The fear is that they will defensively reject borderline applications to protect themselves.

The Numbers Republicans Rarely Lead With

Republicans often talk about the possibility of noncitizens voting. The available evidence suggests the phenomenon is extremely rare, and when it is detected, it is a tiny fraction of the electorate.

Even the examples cited in recent audits and investigations tend to underscore scale, not scandal. Georgia officials said an audit of voter rolls found 20 noncitizens registered to vote. Michigan officials reported 16 noncitizens cast ballots in the 2024 general election. In both states, those figures were fractions of a percentage point compared with millions of registered voters.

Meanwhile, the scale problem for the SAVE Act is not noncitizens. It is citizens without paperwork.

The Brennan Center for Justice reported in a 2023 national survey that 9% of American citizens, about 21.3 million people, do not have ready access to proof of citizenship. The Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement at the University of Maryland has estimated that more than 3.8 million adult citizens lack any form of citizenship document at all, such as a birth certificate, passport, or naturalization papers.

Those gaps are not evenly distributed. Research cited by voting policy analysts shows higher documentation barriers among people of color, young adults ages 18 to 24, and highly mobile Americans who move across state lines and discover that election administration is not one system, but many.

There is also a quiet, paperwork-based vulnerability that can turn into a loud political problem: name mismatches. Married women who have changed their names may have birth certificates that do not match their current legal names. That does not make them any less eligible to vote. However, under a strict document-checking regime, mismatches can become friction, and friction becomes disenfranchisement if deadlines hit first.

Polling Loves ID, Until It Meets the DMV

The politics of voter ID are not complicated. Majorities routinely say they support it.

Pew Research has found broad support for requiring photo identification to vote, including majorities of Democrats and Republicans. Gallup polling has also shown strong support for proof-of-citizenship requirements for first-time registrants.

Michael J. Hanmer, who directs the University of Maryland’s Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement, has argued that voter ID polls well in part because many voters assume the ID they have is sufficient, current, and easy to replace. That assumption breaks down in the margins, where expired IDs, hard-to-find documents, and inconsistent state rules do the real damage.

Hanmer has also emphasized that citizenship verification already exists in the voter registration process, but it operates as what he called “51 separate systems” because states run elections. That is the central contradiction of the SAVE Act: it is sold as a universal fix to a supposedly national problem, but it has to be implemented by dozens of state and local bureaucracies with different databases, different document standards, and different budgets.

States Already Tried Versions of This, and the Courts Noticed

Washington is not inventing proof-of-citizenship fights from scratch. States have been testing these ideas since the mid-2000s, and the outcomes show why the SAVE Act debate is so intense.

Arizona has had a proof-of-citizenship requirement since 2004. A later expansion led to court challenges that reached the Supreme Court. The result has been a split system in which some voters can participate in federal elections but are blocked from state and local races if they have not provided the required document.

Kansas is often cited as a warning label. In 2018, a federal judge struck down the state’s proof-of-citizenship law, finding it violated the Constitution and the National Voter Registration Act of 1993. Court findings in that case showed more than 30,000 voter applications were suspended or cancelled for lacking documentary proof of citizenship, a large share of new registrations after the policy took effect.

New Hampshire, one of the few states not bound by the NVRA, enacted a documentation requirement in 2024. A report by the New Hampshire Campaign for Voting Rights later said more than 240 people were turned away in a non-presidential election year after the law went into effect.

Those cases do not prove the SAVE Act will produce the same outcomes nationwide. They do show what happens when a policy built for edge cases collides with millions of ordinary transactions.

The Leverage Question: Who Blinks First?

In the House, Republicans have repeatedly advanced versions of the SAVE Act. The Senate has been the choke point, and a federal proof-of-citizenship mandate still has an uncertain path there.

That is where the power dynamics get interesting. If the bill stalls again, Republicans can still campaign on it, using Senate resistance as a talking point. If it advances, states get handed an administrative mandate that election experts warn is both expensive and time-consuming, particularly close to a major election cycle.

The Bipartisan Policy Center has argued that states typically need significant lead time to implement major election changes, with about a year described as optimal for large shifts. The SAVE Act is not a single tweak. It is a bundle: registration documents, in-person ID rules, absentee ID copying requirements, and enforcement standards that could change how risk-averse local officials become.

Supporters call that accountability. Opponents call it a bureaucratic chokehold that will be felt most by eligible citizens who already have the least patience, flexibility, money, or documentation.

Either way, the next phase of the fight is not just about what Congress passes. It is about what election offices can realistically execute, and whether a bill sold as “common sense” becomes, in practice, a paperwork-first gatekeeping regime.