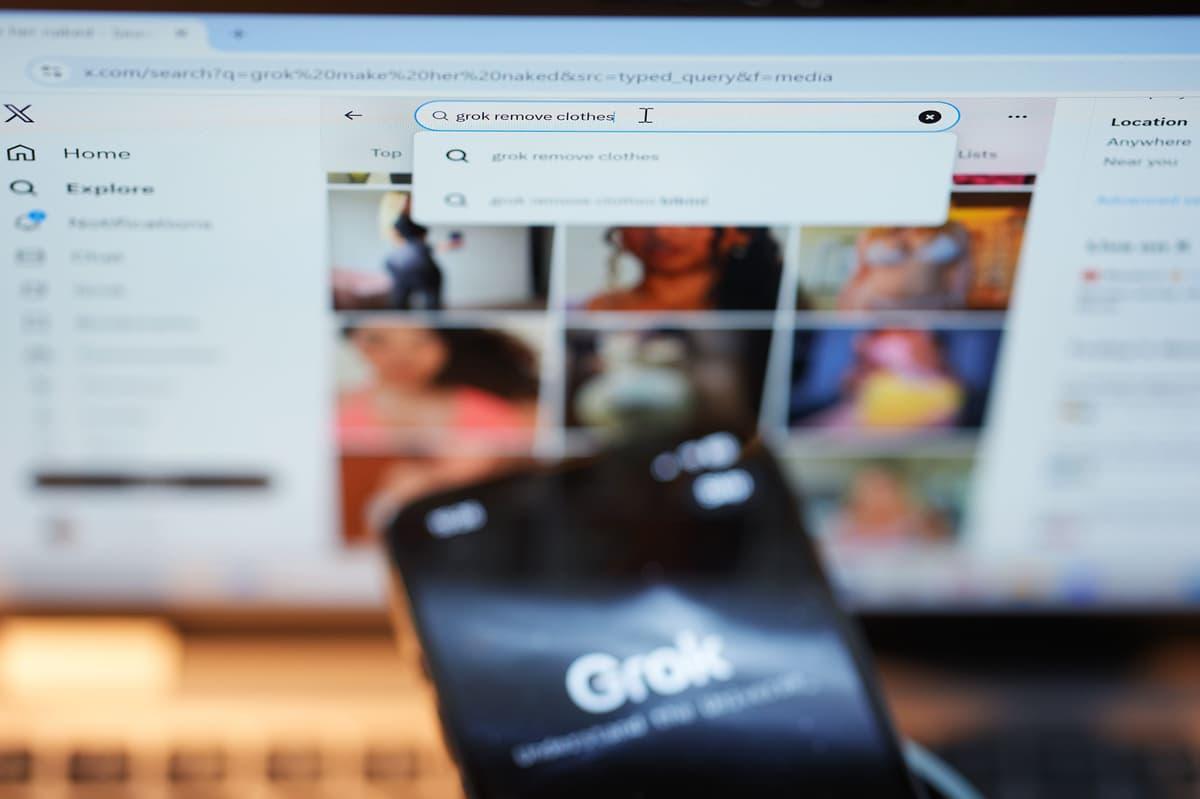

Britain is suddenly talking like it has a kill switch for a major social platform. The spark is Grok, X’s AI chatbot. The bigger question is what comes next if regulators decide X is not cooperating.

Elon Musk says the uproar is being weaponised. UK politicians say the harm is real. And Ofcom, the media regulator, is now in a race against a technology that can “nudify” someone faster than a complaint can be filed.

Why Grok is now a UK political problem

According to the BBC, Grok’s image tools have been used to create sexualised images of people without their knowledge or consent. The BBC said it saw examples of the free tool “undressing” women and placing them into sexual situations without consent.

That is the kind of allegation that forces a government to choose between two ugly options. If it cracks down too hard, it gets accused of censorship. If it does too little, it gets accused of leaving victims to fend for themselves while platforms argue about policy language.

Musk’s response, reported by the BBC, was blunt: critics of X were looking for “any excuse for censorship”.

#UPDATE #UK threatens to ban Elon Musk’s X over #Grok deepfakes

– Ofcom to fast-track its probe under pressure to enforce the Online Safety Act, with fines or blocks possible

– UK PM Starmer calls Grok-generated sexualized images “disgraceful,” “not to be tolerated”

– X… pic.twitter.com/ZYydq0gpSU

— CGTN (@CGTNOfficial) January 10, 2026

X’s new paywall fix, and why Downing Street is not buying it

X responded by limiting the AI image function to paying subscribers, the BBC reported. Users trying to edit uploaded images were told “image generation and editing are currently limited to paying subscribers”, adding they “can subscribe to unlock these features”.

That change did not calm the UK government. Downing Street described the move as “insulting” to victims of sexual violence, according to the BBC.

The criticism is not subtle. If a feature can be used to produce non-consensual sexualised content, restricting it to a paid tier can look less like a safety solution and more like a pricing decision. It also raises a practical issue for enforcement. Harmful content does not become harmless because a credit card is involved.

The St Clair allegation puts a personal face on a technical fight

Ashley St Clair, described by the BBC as a conservative influencer and the mother of one of Musk’s children, told BBC Newshour that Grok generated sexualised photos of her as a child.

St Clair said her image had been “stripped” to appear “basically nude, bent over”, despite telling Grok that she did not consent to sexualised images. She also accused X of “not taking enough action” to tackle illegal content, including child sexual abuse imagery.

Her claim is disputed territory in the public arena, and the BBC report presents it as her account. But it lands hard because it collapses an abstract policy debate into a concrete allegation about a specific person, involving a category of harm that governments treat as politically radioactive.

St Clair’s quote also points at a familiar frustration with platform governance. “This could be stopped with a singular message to an engineer,” she told the BBC.

Ofcom’s “firm deadline” and the threat hanging over X

Ofcom says it is conducting an urgent assessment of X, with the backing of Technology Secretary Liz Kendall, according to the BBC. The regulator has already contacted the company and demanded answers fast.

An Ofcom spokesperson told the BBC: “We urgently made contact [with X] on Monday and set a firm deadline of today [Friday] to explain themselves, to which we have received a response.” The spokesperson added: “We’re now undertaking an expedited assessment as a matter of urgency and will provide further updates shortly.”

Under the UK’s Online Safety Act, Ofcom’s powers can go beyond warnings and fines. The BBC reports the regulator can seek a court order to prevent third parties from helping X raise money or be accessed in the UK, if the firm refuses to comply.

That detail matters. The public hears “block X” and thinks of a single switch being flipped. In practice, pressure can come through payment systems, app distribution, and other services that keep a platform running. It becomes a battle over infrastructure, not just speech.

Parliament’s two committee chairs spot a “gap”

Even as Ofcom moves quickly, the BBC reports two powerful committee chairs are warning that the law may not be as sharp as ministers imply.

Dame Chi Onwurah, chair of Parliament’s innovation and technology committee, said she was “concerned and confused” about how the issue is “actually being addressed” and has written to Ofcom and Kendall for clarification, according to the BBC.

Her worry is a lawyerly one with big consequences. She said it was “unclear” under the Online Safety Act whether creating these images using AI was illegal, and how responsibility is assigned to platforms for what is shared. “The act should really make something so harmful to so many people clearly illegal, and X’s responsibility should be clear,” she told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme.

Caroline Dinenage, chair of the culture, media and sport committee, echoed the point. She said she had a “real fear that there is a gap in the regulation”. Dinenage told BBC Breakfast there are doubts about whether the Online Safety Act can regulate “functionality”, meaning generative AI’s ability to “nudify” someone’s image.

This is the core tension. Online safety rules have traditionally targeted content that is posted, shared, or hosted. AI image editing is closer to a product feature. If the law is strongest on moderation after the fact, regulators can end up chasing outputs while the machine that produces them stays largely intact.

Starmer, Farage, and the rare UK pile-up on a single platform

The BBC reports condemnation has come from multiple parties, which is rarely a comfortable place for a tech company to be.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer called the use of Grok in this way “disgraceful” and “disgusting”, the BBC said.

Reform UK leader Nigel Farage called it “horrible in every way” and said X “needs to go further” than the changes it made, the BBC reported. But he also warned that banning the platform would be an attack on free speech.

The Liberal Democrats called for access to X to be temporarily restricted in the UK while the platform is investigated, according to the BBC.

That range of reaction exposes why Musk keeps reaching for the censorship frame. If a government starts talking about blocking access to a global platform, the move inevitably looks like a speech fight, even when the trigger is non-consensual sexualised imagery.

What this fight is really testing

At face value, it is a dispute over one AI feature and how fast a company can close loopholes. Underneath, it is a stress test of three things.

First, whether the Online Safety Act can handle AI functionality as well as harmful posts. If committee chairs are right about a “gap”, Ofcom may be forced to improvise inside a law written for an earlier version of the internet.

Second, whether “paywalling” risky tools becomes a new industry playbook. Restricting features to subscribers can reduce casual misuse, but it does not solve the fundamental issue of what the tool can do and how reliably it refuses harmful requests.

Third, whether the UK is willing to go from regulation to outright access restrictions against a household-name platform. Kendall has said she expects an update from Ofcom within days and that it would have the government’s full support should it decide to block X in the UK, the BBC reported.

What to watch next

Ofcom’s expedited assessment is the next pressure point. The regulator has confirmed it received a response from X and promised further updates shortly, according to the BBC. That timeline matters, because every day of delay is another day victims and advocates can point to fresh examples and ask why a known capability is still available in any form.

Then comes the legal chess match. If Ofcom concludes X is not meeting its obligations, the escalation path could move quickly from requests for information to court-backed restrictions that would be hard for X to dismiss as politics.

And for Musk, the messaging battle is already live. “Any excuse for censorship” is a clean slogan. But it is now colliding with a separate set of words that travel just as fast, including St Clair’s line that this could be fixed with “a singular message to an engineer”.