The oldest hostage-proof trick in the book is simple. If you have the person, show the person.

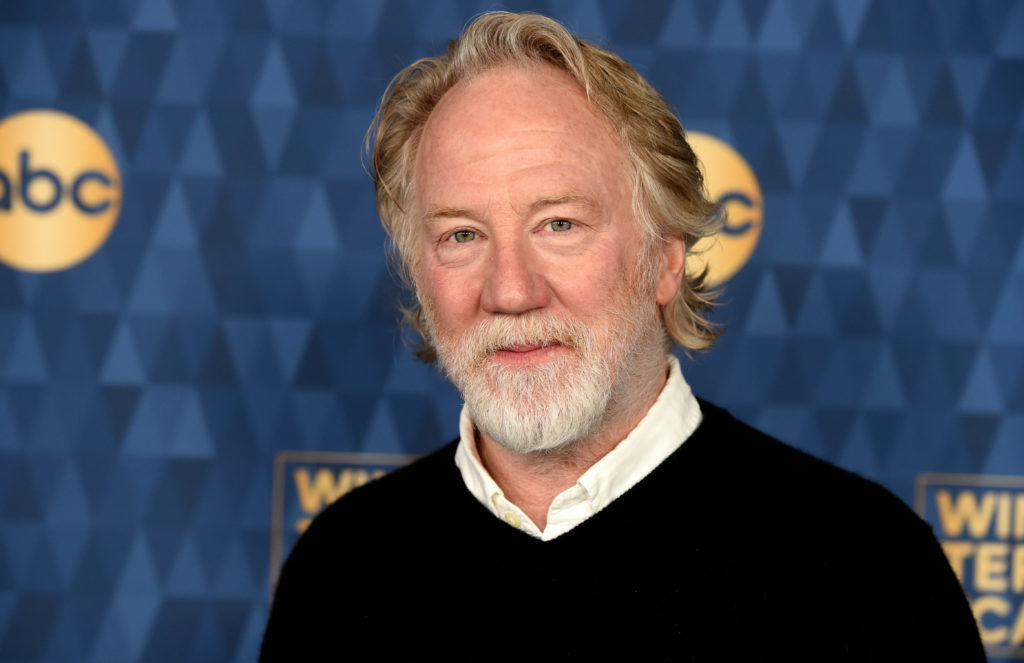

Then Savannah Guthrie went on camera and asked for the modern version of that demand, “proof of life,” while also acknowledging the catch that hangs over every viral case in 2026. Images, voices, and videos can be manufactured fast, cheaply, and convincingly.

That contradiction is the new pressure point in the search for Nancy Guthrie, the 84-year-old mother of the “Today” co-host, who disappeared from her home in the Tucson area in early February 2026, according to PBS NewsHour.

Families want certainty. Investigators want a clean signal. The internet wants content. Meanwhile, scammers want money, and AI gives them better costumes.

A Public Plea, and a Private Problem

In the PBS NewsHour report, Savannah Guthrie appears in a video message, seated between her siblings, addressing whoever has information about their mother. The subtext is unmistakable. The family is trying to open a channel.

She also put the deepfake dilemma into plain language: “We live in a world where voices and images are easily manipulated,” she said.

That is not a throwaway line. It is the entire battlefield. Proof of life used to mean a photo, a short clip, a voice on a phone call, or a coded phrase only the victim would know. Now, each of those can be faked, stitched, or spoofed, especially in a high-profile case where photos and old videos are plentiful.

Former FBI agent Katherine Schweit, quoted in the PBS NewsHour piece, said images shared publicly by family can be repurposed into deepfakes. That is a brutal trade-off. You need the public to look. You also arm the people who want to deceive you.

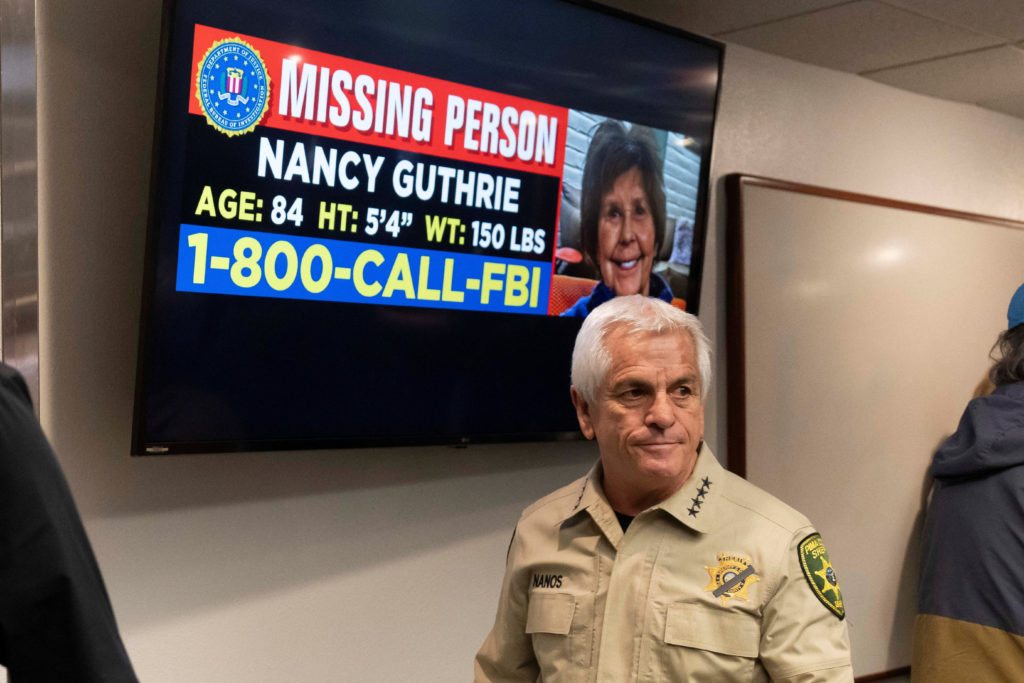

The FBI Warning: Hoaxes Are Part of the Case Now

At a February 5th, 2026, news conference in Phoenix, FBI official Heith Janke laid out the problem investigators are staring at. The FBI has experience with kidnappings, but this era adds a new layer of noise that looks like evidence.

“With AI these days, you can make videos that appear to be very real. So we can’t just take a video and trust that that’s proof of life because of advancements in AI,” Janke said, according to the PBS NewsHour report.

That statement matters for two reasons.

First, it publicly lowers the value of what the public thinks is the gold standard. In past decades, a video was treated like the final receipt. Now, law enforcement is telling everyone, in advance, that a video might not be enough.

Second, it signals that investigators may need more intrusive verification, more technical forensics, and more time. In a case where emotions and attention are already running hot, time is the resource nobody wants to donate.

The PBS NewsHour report also notes the FBI previously warned that people posing as kidnappers can supply what appears to be a real photo or video along with money demands. That turns a famous-name disappearance into an opportunity for freeloading extortionists who never left their couch.

Ransom Notes, Bitcoin Texts, and the Media Megaphone

The case is also a reminder that not every threat is the same threat.

According to PBS NewsHour, at least three news organizations reported receiving purported ransom notes and provided them to investigators, who said they were taking them seriously. Police have not said they received deepfake material related to Nancy Guthrie.

Then came another twist with very 2026 energy. A California man was charged with sending text messages to the Guthrie family seeking bitcoin after following coverage of the case on television, according to a court filing cited by PBS NewsHour. The filing said there was no indication he was suspected of involvement in the disappearance itself.

That split is the whole problem for investigators. Publicity can help surface leads, but it also draws opportunists who create false leads, threaten families, and flood tip lines with junk.

It also creates a power imbalance that is hard to miss. A family with a national platform can speak directly to an alleged kidnapper in a way most families cannot. That visibility can be a tool, but it can also make the family a magnet for scammers who believe fame equals fast cash.

Schweit, in the PBS NewsHour report, framed the public address as tactical. “The goal is to have the family or law enforcement speak directly to the victim and the perpetrator, and ask the perpetrator: What do you need? How can we solve this? Let’s move this forward,” she said.

That is negotiation logic. It is also a high-risk communications strategy in a world where every sentence becomes a clip, every clip becomes a theory, and every theory becomes a cottage industry.

What Counts as Real, and Who Gets to Decide

There is a quieter conflict running underneath the headlines, and it is about authority.

In a kidnapping investigation, the family wants to drive the story because the family has the most at stake. Law enforcement wants to control the story because loose information can compromise searches, trigger copycats, or tip off suspects.

Janke suggested, per PBS NewsHour, that the FBI may have influenced the decision to release the family video, while also drawing a boundary around who ultimately calls the shots.

“We have an expertise when it comes to kidnappings, and when families want advice, consultation, expertise, we will provide that,” he said. “But the ultimate decisions on what they say and how they put that out rests with the family itself.”

Read that again, and you can see the tension baked into the phrasing. The FBI has “expertise.” The family has “ultimate decisions.” In practice, that can mean an aligned strategy, or it can mean parallel campaigns, one aimed at investigative outcomes, the other aimed at the court of public attention.

The deepfake era complicates both. If a suspicious video arrives, investigators might treat it like a potential weapon, not a breakthrough. If law enforcement holds back details to prevent fabrication, the public may interpret the silence as a stall. Everyone is operating with partial information, and the internet is not famous for patience.

The Next 90 Days: Verification Gets Harder, Not Easier

PBS NewsHour reported that investigators said they believe Nancy Guthrie is “still out there,” and they had not identified any suspects at the time of the report.

So what happens next is less about one dramatic clip and more about grinding verification. It is forensics and phone records, camera footage, canvassing, and tips that have to be checked, even when they sound ridiculous.

Schweit put the workload plainly in the PBS NewsHour report: “Investigative techniques accumulate over time,” she said, adding, “Nothing can be dismissed. Everything has to be run to ground.”

That is the reality behind the “proof of life” slogan. The public wants a single artifact that ends doubt. Law enforcement, facing deepfakes and hoaxes, is telling everyone that one artifact might not end anything.

The thing to watch is not whether a video appears online. It is whether investigators can authenticate any communication, separate extortion from evidence, and keep the search from getting buried under the digital confetti that high-profile cases now attract by default.