He promised safety. He marketed “backed” investments. He urged people to tap retirement money. Now the key question is not whether the pitch was real, but how much of the cash is still findable.

Federal prosecutors say Georgia financial adviser Todd Burkhalter has pleaded guilty to wire fraud in a $380 million Ponzi scheme that allegedly hit more than 2,000 people. The case combines a familiar fraud playbook with a very specific, very modern twist: a retirement-and-credit-card squeeze on everyday investors, paired with luxury purchases that are easy to describe but hard to unwind.

The Guilty Plea That Turned a Sales Pitch Into a Federal Case

Burkhalter, identified by prosecutors as the founder and CEO of Drive Planning LLC, pleaded guilty to wire fraud in federal court, according to CBS News reporting on the announcement from federal authorities. Prosecutors alleged the scheme totaled $380 million and involved more than 2,000 victims.

ATLANTA – Todd Burkhalter, the founder and chief executive officer of the Georgia-based financial advisory group Drive Planning LLC, has pleaded guilty to wire fraud for masterminding a years-long Ponzi scheme that allowed him to live a lavish lifestyle while causing thousands of… pic.twitter.com/OVG2Tf5WGG

— US Attorney NDGA (@NDGAnews) January 21, 2026

Burkhalter, 54, is from St. Petersburg, Florida, CBS News reported. He was represented by the federal defenders’ office, and a message to that office after hours was not immediately returned, according to the same report.

The Investment Hook: ‘Short-Term’ Loans and Big Promised Returns

Prosecutors said one of the investment offerings was pitched as short-term loans to real estate developers, promising returns of 10% every three months, according to CBS News. Prosecutors also alleged Burkhalter falsely claimed the investments were backed by real estate holdings.

That 10% quarterly figure matters because it is designed to sound both lucrative and routine. Ten percent every three months is not a normal “sleep at night” return. Sustained over a year, it implies a return well north of typical market benchmarks, the kind of number that can make skeptics pause and hopeful savers lean in.

Where Prosecutors Say the Money Went: Yacht, Mexico Condo, Motorcoach

Prosecutors accused Burkhalter of using investor funds in part to buy luxury items, including a $2 million yacht, a $2.1 million condo in Mexico, and a motorcoach, as detailed by CBS News.

Financial advisor Todd Burkhalter admits to running $380M Ponzi scheme — largest in Georgia history — to fund lavish lifestyle https://t.co/150BJcYbjN pic.twitter.com/RHrPIwPT3d

— New York Post (@nypost) January 22, 2026

Those purchases are more than gossip-worthy props. They are the type of assets a court-appointed official can try to sell to push money back toward victims. But even in the best scenario, liquidation is slow, values fluctuate, and proceeds rarely match headline numbers once legal costs and other claims stack up.

The Victims’ Pressure Point: Retirement Accounts and Borrowed Money

Prosecutors said Burkhalter encouraged investors to dip into retirement accounts and savings and even take out lines of credit, according to CBS News. That detail goes straight to why the fallout can be lasting. When people borrow to invest, losses can keep accruing even after the scheme stops, through interest payments and damaged credit.

It also mirrors a warning sign regulators and investor-protection groups frequently emphasize: fraudsters often steer victims toward “found money” sources like 401(k) rollovers, home equity, or new credit lines because it increases the pool of investable cash quickly.

For readers who want a plain-English breakdown of what defines a Ponzi scheme and why “steady high returns” are a recurring trap, the SEC’s investor education page on Ponzi schemes at Investor.gov lays out the mechanics and common red flags.

Another Guilty Plea in the Orbit

Drive Planning’s former chief operating officer has also pleaded guilty, according to CBS News. Prosecutors often use cooperation from insiders to map where money moved, who signed off on what, and which representations were made to investors. But a second plea can also raise uncomfortable questions about internal controls and how long the business model functioned before anyone hit a stop button.

What Federal Authorities Said Out Loud

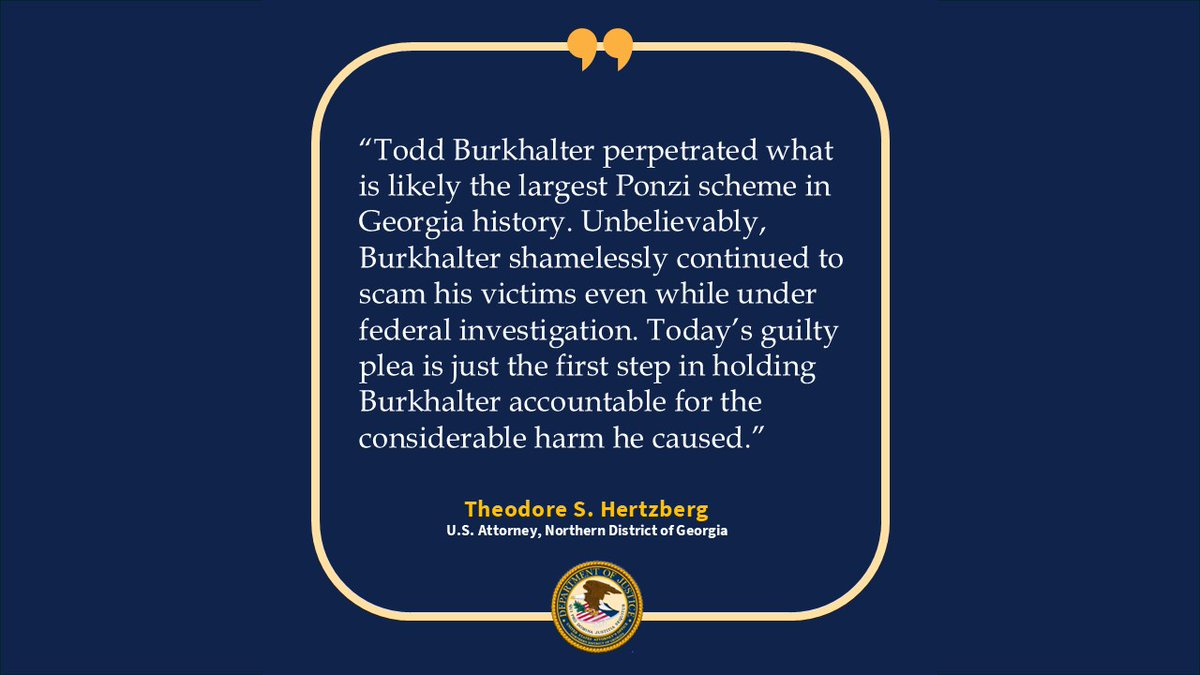

At a news conference announcing the plea, Aaron Seres, identified as a supervisory special agent at the Atlanta-area FBI office, offered a blunt forecast for victims. “These losses will echo through the lives of these victims long after these defendants receive their well-deserved sentences,” Seres said, according to CBS News.

“Todd Burkhalter built a massive Ponzi scheme on lies, exploiting trust to steal hundreds of millions of dollars from more than 2,000 victims while funding an extravagant lifestyle,” said Paul Brown, Special Agent in Charge of FBI Atlanta. “The FBI will continue to aggressively… pic.twitter.com/xMfjik6uVq

— FBI Atlanta (@FBIAtlanta) January 21, 2026

That quote does two jobs at once. It frames sentencing as only one chapter, and it hints at the real-world time horizon for people trying to rebuild savings, retirement timelines, and trust.

The Time on the Table: Prosecutors Point to More Than 17 Years

As part of a plea agreement, prosecutors plan to recommend a sentence of more than 17 years in prison for Burkhalter, U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Georgia Theodore Hertzberg said, according to CBS News.

Recommendations are not the same as final sentences. Federal judges consider sentencing guidelines, the plea terms, victim impact, and other statutory factors. Still, “more than 17 years” is a clear signal of how the government is sizing up the scale and severity described in the case.

The Hardest Part: Clawbacks, Asset Sales, and the Odds of Being Made Whole

Hertzberg said a court-appointed official is trying to recover victims’ money by selling Burkhalter’s assets, but it is “highly unlikely” victims will get back everything they lost, according to CBS News.

This is the part fraud headlines rarely capture. Even when investigators trace funds, there can be competing claims, depreciated assets, and money that is simply gone. In many Ponzi cases, recovery also involves “clawback” actions, where courts pursue certain transfers made before the collapse, sometimes even from investors who thought they were receiving legitimate profits. Each case turns on its own facts and the structure of the scheme.

What To Watch Next

Three things typically determine how this story evolves from here.

First, sentencing. Prosecutors have telegraphed their recommendation, but the court’s final decision will be the definitive marker of how the justice system weighs the conduct described.

Second, recovery efforts. Asset sales can bring in real money, but the timeline can stretch, especially if property is held abroad or tied up with other obligations. Victims will be watching for updates from the court-appointed process that Hertzberg described.

Third, further accountability. With a former chief operating officer already pleading guilty, victims and regulators will likely scrutinize how the business was presented, how funds were handled, and who else had decision-making authority.

Burkhalter’s guilty plea puts the core allegation into a single sentence. But the next phase is where the stakes become personal, measured in years of prison exposure on one side and the slow arithmetic of financial recovery on the other.